Watercolor background: the complete guide in 10 examples

To create strong watercolor backgrounds, I follow two principles:

1

I preserve or amplify the beauty and the unique characteristics of watercolor: flow of water and transparent pigments on white, luminous and textured paper

2

I establish a strong contrast between foreground and background. The contrast is established through differences in detail (abstract background to detailed foreground), color, tonal values and texture.

Let’s see how this works in practice through 10 examples.

—

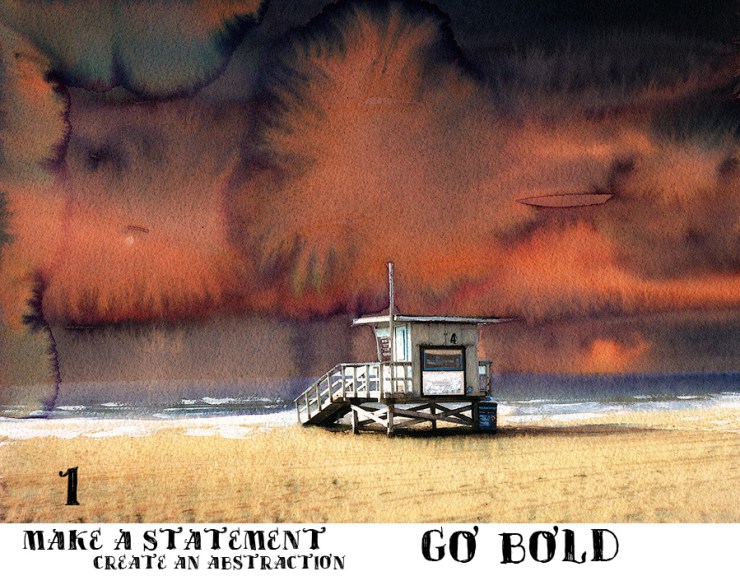

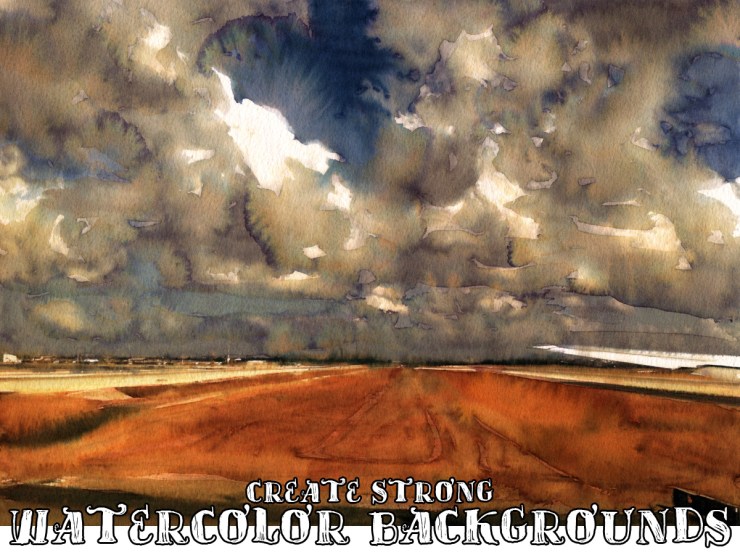

Watercolor background example #1

Making a statement

When painting Zuma Beach, I knew my subject had been done many times. I needed a powerful background to make the watercolor work. I decided to turn the background into the real focus of the watercolor.Â

Thinking of my watercolor background as an oversized abstraction helped liberate the movement of my brush. Going bold was the best way to turn this piece into something worth looking at.

—

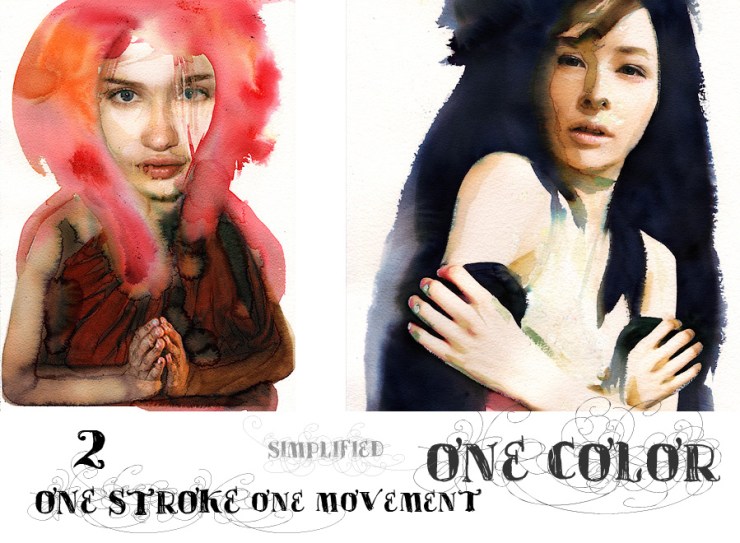

Watercolor background examples #2 and #3

One brushstroke

To feel free to go bold when painting a watercolor background, I like to simplify everything else to the greatest extent possible. My initial goal is always to paint the background with a single brush stroke. This means using large brushes, sturdy and predictable paper and copious amounts of water to do the work for me.

- My brush is a large mop that can hold a point and an edge. I use the Winsor & Newton Goat Hair Wash Brush (Series 140), an affordable mop that holds tons of water yet gives me enough of a point to deal precisely with the edges of the background watercolor wash.

- I use Arches’ full cotton, hand molded and cold press paper because it handles any volume of water.

- The more water in the wash, the higher the contrast with the precise strokes I will use for the foreground. Water also has a way to create the happy accidents that give character to the background. I use the largest container I can find to hold the water, knowing I will not be able to replace it once I get started.

- Finally, I plan carefully so that painting the watercolor background takes only a few seconds and a single movement.

In the two portraits below, the hair surrounding the faces is effectively the abstract background used to guide you to the eyes of the model. In both cases, one or two brush strokes were enough once water had been applied to paper.

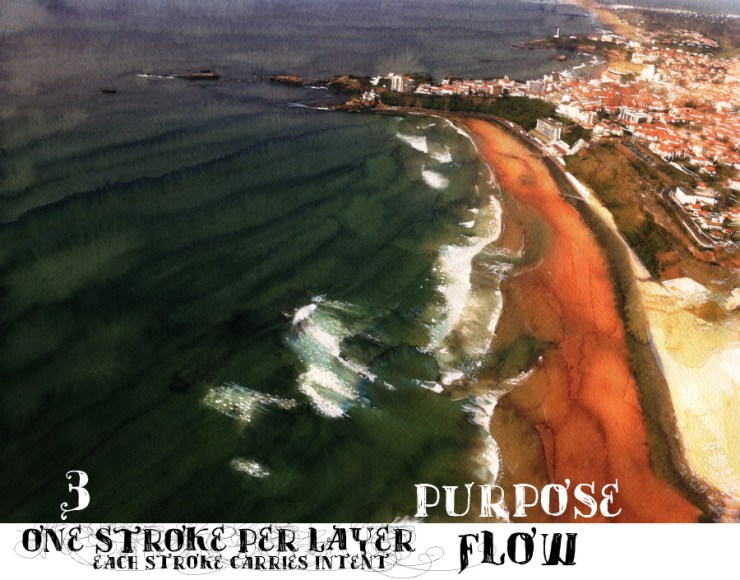

There are of course many exceptions to the one brushstroke mantra. In this landscape and aerial view of Biarritz, I simulated the swell hitting the beach by using multiple layered brush strokes, starting from the distance and increasing in density (of both strokes and color) as you get closer to the beach. In that case, multiplying the brushstrokes didn’t hinder flow and it served a direct purpose for the composition.

—

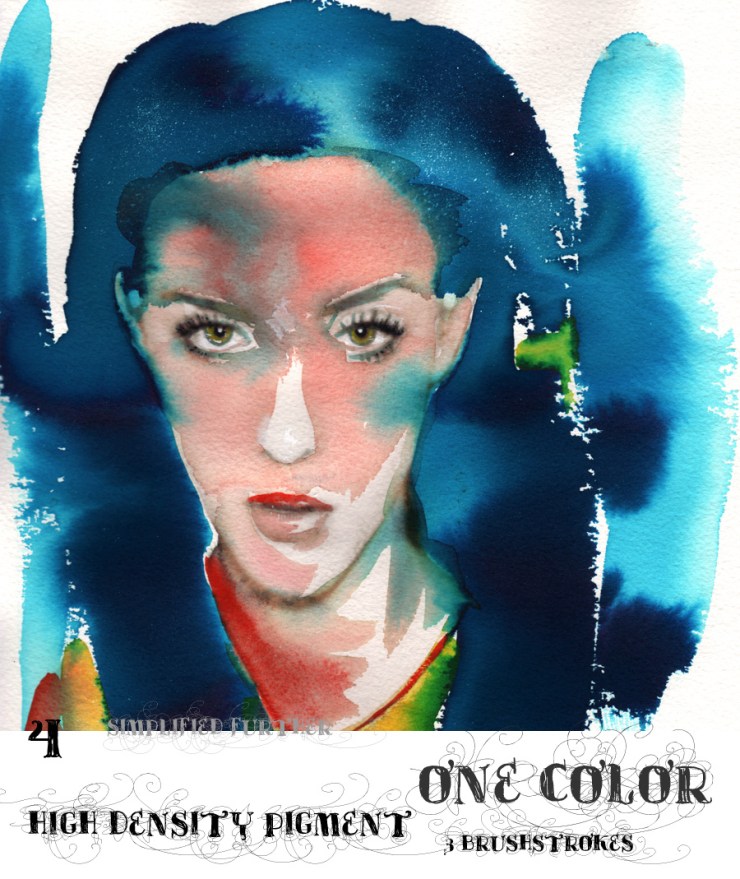

Watercolor background example #4

Simplify further: more pigment density, less colors

When making chocolate chip cookies, I like to use the best and most concentrated chocolate possible, rather than multiply the number of chocolate chips. The same goes with watercolor, where I:

- Use the highest quality pigments I can afford. Among my favorites are the affordable, high density / high stability Yarka pigments.

- Use dried pigments that I can sprinkle in specific areas of the watercolor background in order to establish greater contrasts of color and tonality. Old watercolor pans and tubes are a great source of dried up and otherwise useless pigments.

- Keep the mixing of colors to a bare minimum. One color backgrounds are great; two color ones require you to know what you are doing and plan ahead. Three colors -a bad idea.

I often stick to a one color background, mixed and merging with either a deep black (using India ink) or a white background. This provides me with enough tonal values and complexity without muddying the results or clashing with the foreground.

In our first example, Zuma Beach, a red and India ink was all I needed for the background.Â

In the portrait below, I framed and created the background for the face using a simple one-color background which echoes in the colors used for the face itself and dilutes into the white of the paper.

The hair and background become a single abstraction that reinforces the composition. In the top part of the hair, you can see texture created by applying salt -which brings us to our fourth example.

—

Watercolor background example #5

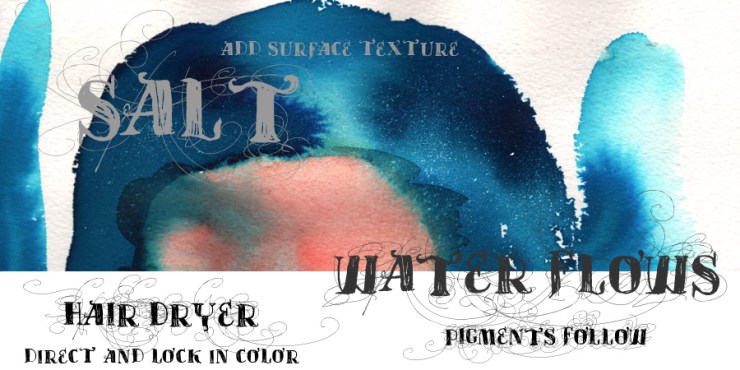

Salt, tape, masking fluid, sponges, paper towels, a hair dryer and dry brushes

That seemingly random list of accessories is actually a list of tools I use to remove water from my wash, with control.

Salt allows me to remove pigments in precise areas of the painting. It also helps create structure. I use it to more precisely achieve the tonal balance I need in my background.

Tape and masking fluid allow me to keep areas dry. I apply them, work on the wash and let the wash dry. Then I can remove tape and masking fluid and work the dry,virgin areas.

Sponges, paper towels and dry brushes allow me to lift water when and where required. I try to rarely use them, because lifting water only means I went wrong when using your mop -and the mistake will show. There are a few instances when removing water makes sense though:

- Lifting water can help direct the flow of pigment to a specific part of the background

- Removing water increases pigment density

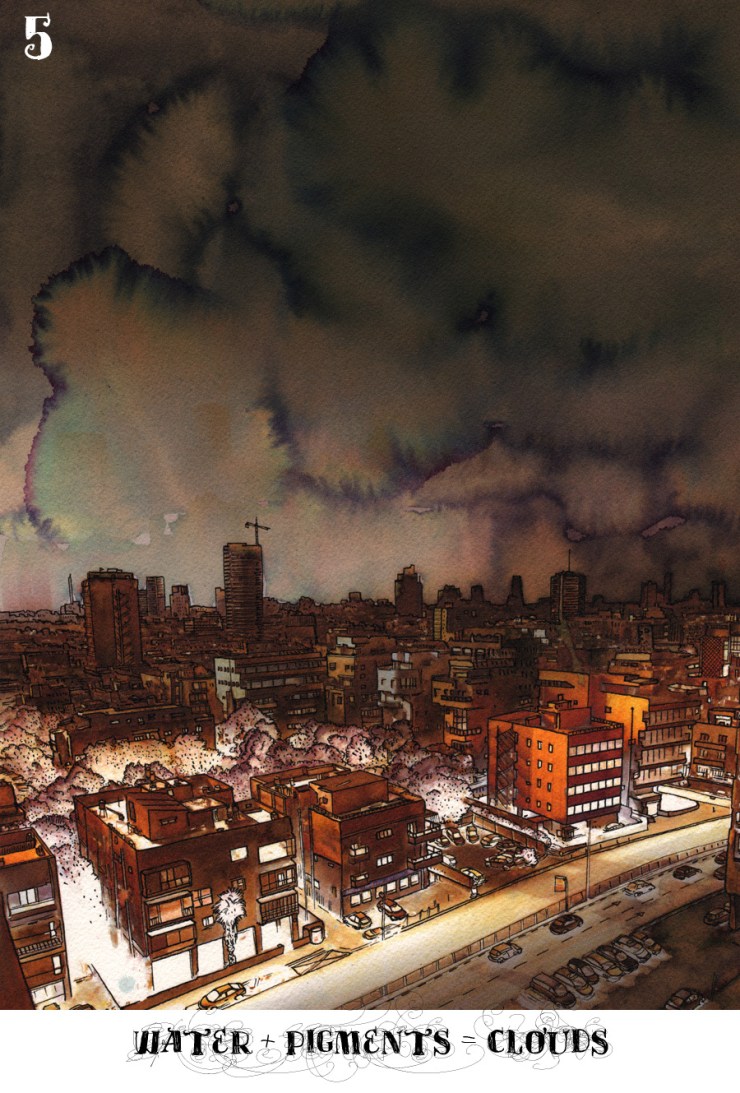

In this landscape of Tel Aviv, I used sponges and the application of multiple washes to create a structured background that allowed me to intensify the dark to light and abstract to detail transition to the foreground.

—

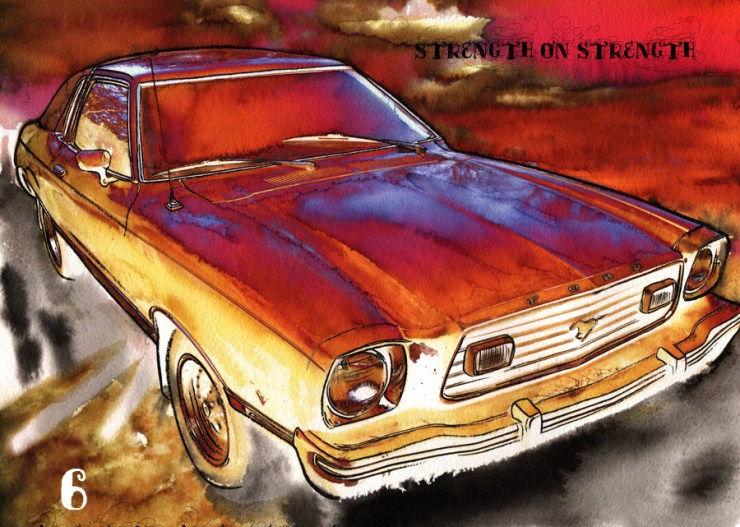

Watercolor background example #6:

Start with your strongest color

If I start weak by using washed out or pastel colors, adding color later on becomes impossible without multiplying layers and weakening the overall painting. I hit as high as I can in terms of color intensity and work down, not up, from my starting point. This is how I  used this technique to establish a muscle color palette and background for a muscle car:

Â

Â

—

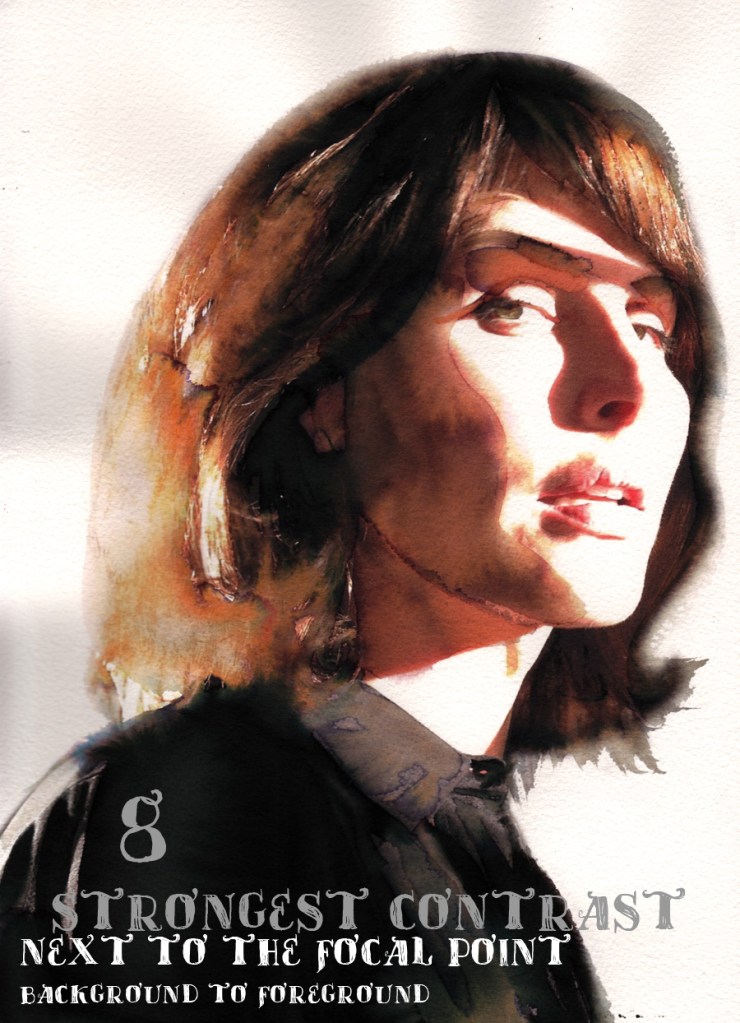

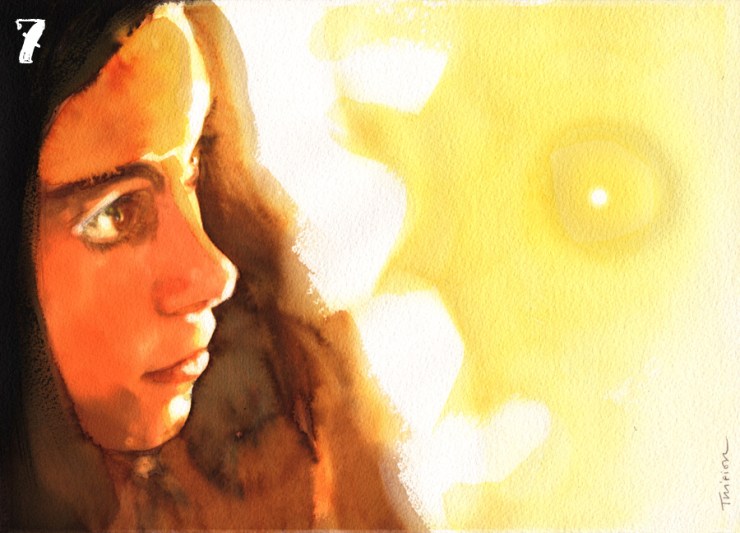

Watercolor background examples #7 and #8:

Light to dark boundaries

When establishing my background, I am always very aware of the light to dark transitions. A strong contrast and clean boundaries are key to establish the composition, yet watercolor is a messy medium if you paint freely. To solve the conflict, I establish a composition that allows me to paint the watercolor in a single session while creating clear and high contrast boundaries between the foreground and background.

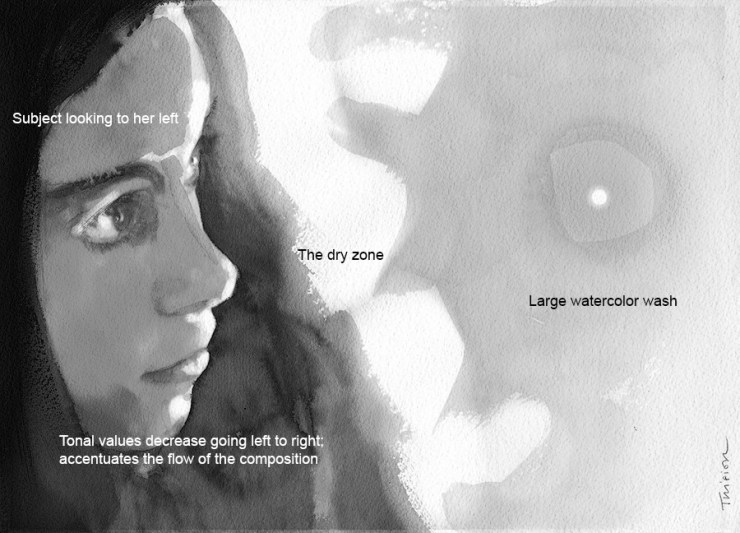

In this portrait for instance:

- The subject is looking to its left

- Tonal values go from dark to light in a left to right direction, following the subject’s gaze -however

- The tonal values are lightest where the subject’s face and hair meet the background

The composition allowed me to establish a dry zone between the foreground and the portrait. The background could then be painted freely to reinforce the whole.

Here is another example of the same technique, this time to clearly separate a face from the wash used for the hair:

For this portrait, the composition allows dry (unpainted) paper to establish the boundary with the dark wash used for the hair. Two benefits can be derived:

- No pigment contamination between the face and the hair

- Maximum contrast near the focal point to maximize the readability of the composition and strength of the portrait

—

Watercolor background example #9:

Flow and movement

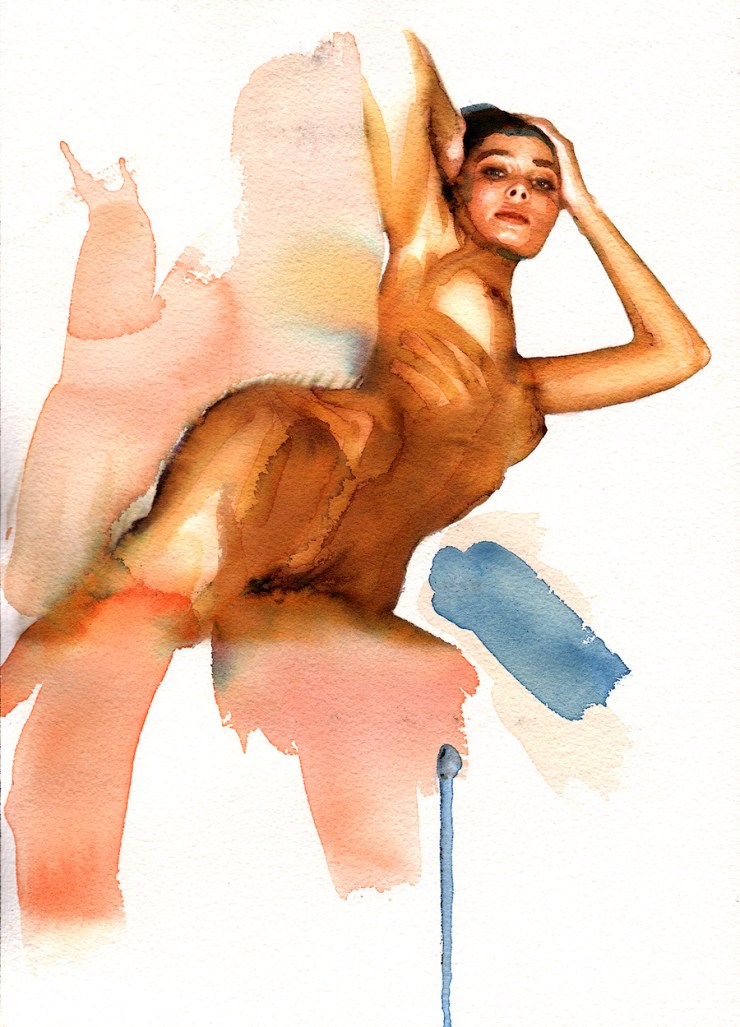

Here is a nude where the wash used for the background combines with the one used for the foreground. While the colors are fairly similar, the composition still works and the foreground is clearly separated from the background.

In that case, four single brushstrokes and the the flow of water and pigment create the frame within the frame that guides the eye of the viewer to the eyes of the model.

—

Watercolor background example #10:Â

Texture

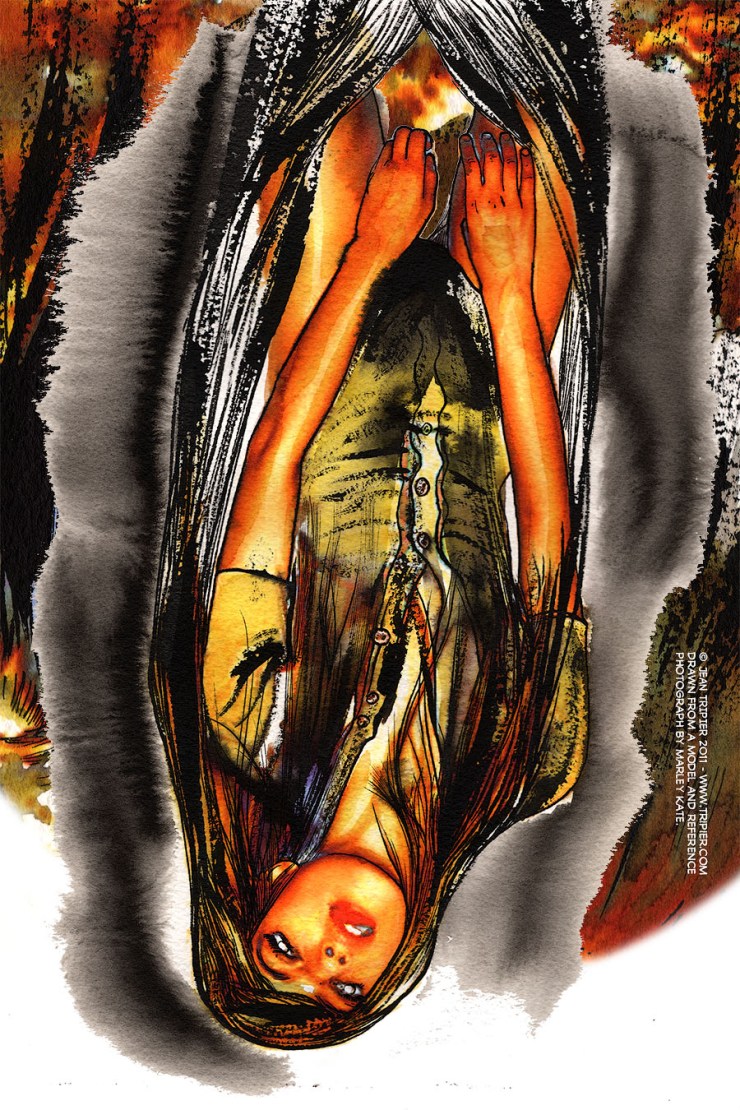

In “Falling” below, I wanted texture to help establish the contrast between the model and her background. The dry brush technique used to paint the hair, and the black ink wash surrounding the hair, create a separation of style and texture.

The original watercolor stops at the wash -the additional colored background was added to the image via Photoshop.

—

In conclusionÂ

There are only two rules

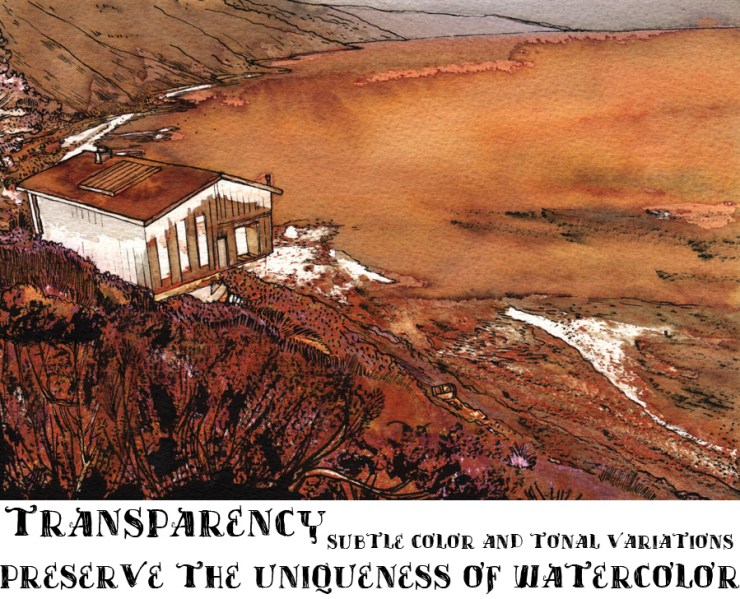

In the end, it pays to follow the two rules I outlined initially. If I clearly establish my foreground to background contrast, and if I preserve the unique transparency and subtlety of watercolor, things usually work. Everything else can be ignored.

When I painted Big Sur (below), I wanted a serene yet somewhat gloomy atmosphere that a bold and colorful background would have made impossible to establish.

I created a transparent but closed background, hiding the sky to bring you into a more claustrophobic view of the sea. The contrast was established by detailing the foreground and reserving my darkest black for the bottom part of the paper.

There was no need to make a statement because my goal was simply to establish a mood. Creating transparent layers while establishing a strong contrast from foreground to background was enough.

I hope those examples will help you achieve great results. Please comment below if you have beer advice or have questions. You can also find more watercolor tips and techniques in my complete watercolor techniques guide. You will see that several of the watercolor portraits I show as examples in my guide use those techniques in multiple variants. Now it’s your turn!

Discussion (16) ¬

love the boldness!

great ideas and technique…love the looseness!

When you did the portraits, (#8) did you draw the face out in pencil first… what was the process in that. Also with the landscape, was the ink work done first then the watercolor? Thank you for your advice

Hi Jeanne, to answer your questions:

1. The shape of the face is done in pencil first, very lightly. Then the hair and blouse, which are used to frame and define the face. Then the different details of the face. This way the wash used for the hair doesn’t bleed into the face.

2. Ink first, because otherwise it bleeds into the watercolor -no matter how long I wait for the paper to dry.

Ah yes love this!!! But how are you combining the photographs?

I will sometimes scan a watercolor, eliminate part or all of the background in Photoshop and replace it with another background. So you are effectively looking at a composite of two images.

Hi Jean. I recently found your site. Love at first sight! Your work is mesmerizing! Do you ever offer any workshops, online classes, etc.?

Hi Angie,

I am flattered you would consider any form of instruction from me; sorry, at this point I do not run any form of workshop. Maybe in the future! Thanks for inquiring.

This is very helpful..thank you!

Thanks for sharing! Very nice and … thoughtful!

Thank you. Fantastic!

Great helpful tips!

Great examples!

May I use your technique to show how to paint clouds in a upcoming free watercolor class at our senior center?

Thanks, Ken